Across the United States, bats face many threats that put them at severe risk of population decline. These threats include a devastating disease called white-nose syndrome, wind energy, habitat loss, and climate change.

Watch the video below to learn more about white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that is often fatal to hibernating bats. This disease does not affect humans, livestock, or other wildlife.

Report your bat observations

Public reports of groups of bats (colonies), and sick, injured, or dead bats provide valuable information to track bat populations in Washington. Report bat colonies, sick or dead bats to help research efforts in Washington.

Found a bat? Learn how to safely move them or reach out for help from a wildlife rehabilitator.

For more information on how to remove a bat from your home or to exclude them from buildings, visit our Living with Wildlife webpage.

What is white-nose syndrome?

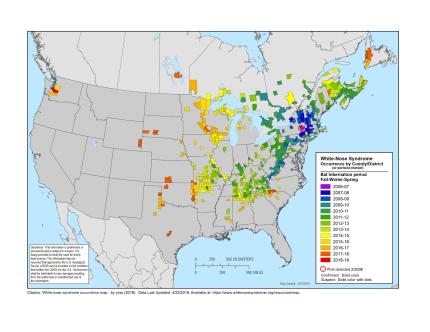

White-nose syndrome is a disease caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The disease is estimated to have killed millions of bats in eastern North America since 2006 and can kill up to 100% of bats in a colony during hibernation.

In March 2016, the first case of white-nose syndrome in the western U.S. was confirmed in a little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) near North Bend in King County. Though the disease has devastated bat populations in eastern North America, we do not yet know how it will impact western bats. In general, bats in Washington do not hibernate in large groups like eastern North American bats. Thus, the spread of the disease in western states may be different.

The fungus can grow on the nose, wings, and ears of an infected bat during winter hibernation, giving it a white, fuzzy appearance. Once the bats wake from hibernation, this fuzzy white appearance goes away. Even though the fungus may not be visible, it invades deep skin tissues and causes extensive damage.

Affected bats arouse more often during hibernation which causes them to use crucial fat reserves, leading to possible starvation and death. Additional causes of mortality from the disease include wing damage, inability to regulate body temperature, breathing disruptions, and dehydration.

Learn more about white-nose syndrome and what researchers around the country are doing to prevent the spread of the disease at whitenosesyndrome.org.

Where is white-nose syndrome in Washington?

Counties with confirmed cases of white-nose syndrome

- Benton

- Chelan

- Jefferson

- King

- Kittitas

- Lewis

- Pierce

- Snohomish

- Thurston

- Yakima

Counties confirmed to have the fungus present that causes white-nose syndrome

- Benton

- Chelan

- Clallam

- Clark

- Grant

- Grays Harbor

- Island

- Jefferson

- Kitsap

- Klickitat

- King

- Kitsap

- Kittitas

- Lewis

- Mason

- Okanogan

- Pierce

- Skagit

- Snohomish

- Thurston

- Whatcom

- Yakima

Affected bat species in Washington

White-nose syndrome has been confirmed in the following bat species in Washington:

- Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus)

- Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis)

- Western long-eared bat (Myotis evotis)

- Fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes)

Additionally, the silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans), California myotis (Myotis californicus), big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), and Long-legged myotis (Myotis volans) have been documented in Washington to carry the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome.

Latest news release (September 2024): New cases of white-nose syndrome recorded in Washington bats this year

How the fungus spreads

The fungus that causes white-nose syndrome is harmful to bats but not humans, livestock, or pets.

Though the fungus is believed to be primarily transferred via bat-to-bat or bat-to-environment contact, it can also be inadvertently spread by humans. People can carry fungal spores on clothing, shoes, or recreation equipment that comes into contact with the fungus. Properly decontaminating shoes, clothes, and equipment used in areas where bats live is critical to reduce the risk of spreading white-nose syndrome.

Visit whitenosesyndrome.org to learn how to properly decontaminate your equipment.

The fungus can survive in the environment of underground hibernacula (like caves and mines) for years, and scientists are currently researching how persistent it is in other environments where bats roost such as cliffs, attics, or under bridges.

Winter hibernating areas may serve as reservoirs for the fungus. Bats that use or even briefly visit these hibernating spots could deposit or pick up the fungus and move it to other areas where bats live. Identifying these types of environmental hot spots for the fungus, and how bats may be coming in contact with and moving the fungus across the landscape, is an important part of reducing the spread of white-nose syndrome in Washington bats.

How you can help

- Report groups of bats you see using the online observation reporting form. This information will help us understand our bat populations and monitor white-nose syndrome in Washington.

- Do not handle live bats. If you have found a sick or dead bat, please report it using the online reporting form and contact the closest wildlife rehab facility (see the list below).

- Avoid entering areas where bats may be living to limit the potential of transmitting the fungus that causes the disease and disturbing vulnerable bats. Do not allow pets to access areas where bats may be roosting or overwintering as they may carry the fungus to new sites.

- Get involved in bat conservation! Use our Creating Bat Habitat resources to improve habitat for bats in your area. You can start by reducing lighting around your home, minimize tree clearing, and protect streams and wetlands. Try to incorporate one or more snags into your landscape, keeping old and damaged trees when possible. Snags provide important habitat for bats and other backyard wildlife.

For more information on living with bats, and instructions for how to install a bat house (PDF), download the "Living with Wildlife: Bats" publication.

Bat rehabilitators

Please note: Only PAWS Wildlife Center and Happy Valley Bats are approved to rehabilitate bats with signs of white-nose syndrome.

Grant County

- Center Washington Wildlife Hospital, 509-450-7016

Jefferson County

- Center Valley Animal Rescue, 360-765-0598

King & Snohomish counties

- PAWS Wildlife Center, 425-412-4040

Snohomish County

- Ogaard Bat Rehabilitation, 425-481-7446

- Happy Valley Bats, 360-631-0668

- Sarvey Wildlife Care Center, 360-435-4817

Whatcom County

- Whatcom Humane Society Wildlife Rehabilitation Services, 360-966-8845

Whitman County

- WSU Exotics and Wildlife Ward, 509-335-0711

Why bats matter to our environment and economy

Bats are valuable members of ecosystems around the world, saving farmers in the U.S. alone over $3 billion each year in pest control services. One colony of bats can consume many tons of insects that would otherwise eat valuable crops, or threaten human health and well-being. Some bat species eat moths or beetles that are harmful forest pests.